---

layout: global

displayTitle: Spark Streaming Programming Guide

title: Spark Streaming

description: Spark Streaming programming guide and tutorial for Spark SPARK_VERSION_SHORT

---

* This will become a table of contents (this text will be scraped).

{:toc}

# Overview

Spark Streaming is an extension of the core Spark API that enables scalable, high-throughput,

fault-tolerant stream processing of live data streams. Data can be ingested from many sources

like Kafka, Flume, Twitter, ZeroMQ, Kinesis or TCP sockets can be processed using complex

algorithms expressed with high-level functions like `map`, `reduce`, `join` and `window`.

Finally, processed data can be pushed out to filesystems, databases,

and live dashboards. In fact, you can apply Spark's

[machine learning](mllib-guide.html) and

[graph processing](graphx-programming-guide.html) algorithms on data streams.

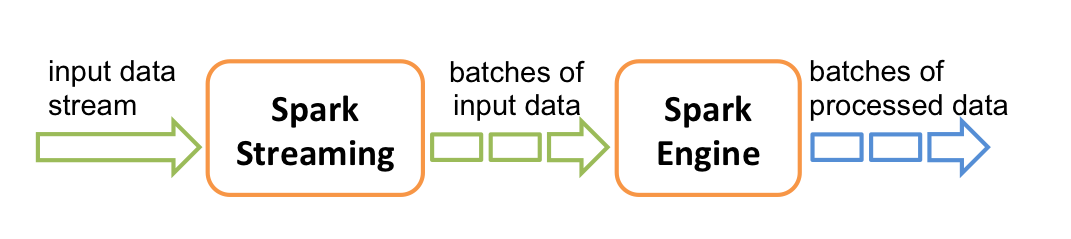

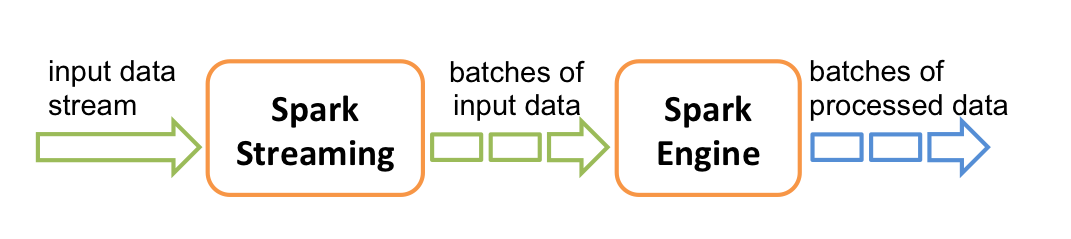

Internally, it works as follows. Spark Streaming receives live input data streams and divides

the data into batches, which are then processed by the Spark engine to generate the final

stream of results in batches.

Spark Streaming provides a high-level abstraction called *discretized stream* or *DStream*,

which represents a continuous stream of data. DStreams can be created either from input data

streams from sources such as Kafka, Flume, and Kinesis, or by applying high-level

operations on other DStreams. Internally, a DStream is represented as a sequence of

[RDDs](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.rdd.RDD).

This guide shows you how to start writing Spark Streaming programs with DStreams. You can

write Spark Streaming programs in Scala, Java or Python (introduced in Spark 1.2),

all of which are presented in this guide.

You will find tabs throughout this guide that let you choose between code snippets of

different languages.

**Note:** Python API for Spark Streaming has been introduced in Spark 1.2. It has all the DStream

transformations and almost all the output operations available in Scala and Java interfaces.

However, it has only support for basic sources like text files and text data over sockets.

APIs for additional sources, like Kafka and Flume, will be available in the future.

Further information about available features in the Python API are mentioned throughout this

document; look out for the tag

Python API.

***************************************************************************************************

# A Quick Example

Before we go into the details of how to write your own Spark Streaming program,

let's take a quick look at what a simple Spark Streaming program looks like. Let's say we want to

count the number of words in text data received from a data server listening on a TCP

socket. All you need to

do is as follows.

First, we import the names of the Spark Streaming classes, and some implicit

conversions from StreamingContext into our environment, to add useful methods to

other classes we need (like DStream). [StreamingContext](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.streaming.StreamingContext) is the

main entry point for all streaming functionality. We create a local StreamingContext with two execution threads, and batch interval of 1 second.

{% highlight scala %}

import org.apache.spark._

import org.apache.spark.streaming._

import org.apache.spark.streaming.StreamingContext._ // not necessary in Spark 1.3+

// Create a local StreamingContext with two working thread and batch interval of 1 second.

// The master requires 2 cores to prevent from a starvation scenario.

val conf = new SparkConf().setMaster("local[2]").setAppName("NetworkWordCount")

val ssc = new StreamingContext(conf, Seconds(1))

{% endhighlight %}

Using this context, we can create a DStream that represents streaming data from a TCP

source, specified as hostname (e.g. `localhost`) and port (e.g. `9999`).

{% highlight scala %}

// Create a DStream that will connect to hostname:port, like localhost:9999

val lines = ssc.socketTextStream("localhost", 9999)

{% endhighlight %}

This `lines` DStream represents the stream of data that will be received from the data

server. Each record in this DStream is a line of text. Next, we want to split the lines by

space into words.

{% highlight scala %}

// Split each line into words

val words = lines.flatMap(_.split(" "))

{% endhighlight %}

`flatMap` is a one-to-many DStream operation that creates a new DStream by

generating multiple new records from each record in the source DStream. In this case,

each line will be split into multiple words and the stream of words is represented as the

`words` DStream. Next, we want to count these words.

{% highlight scala %}

import org.apache.spark.streaming.StreamingContext._ // not necessary in Spark 1.3+

// Count each word in each batch

val pairs = words.map(word => (word, 1))

val wordCounts = pairs.reduceByKey(_ + _)

// Print the first ten elements of each RDD generated in this DStream to the console

wordCounts.print()

{% endhighlight %}

The `words` DStream is further mapped (one-to-one transformation) to a DStream of `(word,

1)` pairs, which is then reduced to get the frequency of words in each batch of data.

Finally, `wordCounts.print()` will print a few of the counts generated every second.

Note that when these lines are executed, Spark Streaming only sets up the computation it

will perform when it is started, and no real processing has started yet. To start the processing

after all the transformations have been setup, we finally call

{% highlight scala %}

ssc.start() // Start the computation

ssc.awaitTermination() // Wait for the computation to terminate

{% endhighlight %}

The complete code can be found in the Spark Streaming example

[NetworkWordCount]({{site.SPARK_GITHUB_URL}}/blob/master/examples/src/main/scala/org/apache/spark/examples/streaming/NetworkWordCount.scala).

First, we create a

[JavaStreamingContext](api/java/index.html?org/apache/spark/streaming/api/java/JavaStreamingContext.html) object,

which is the main entry point for all streaming

functionality. We create a local StreamingContext with two execution threads, and a batch interval of 1 second.

{% highlight java %}

import org.apache.spark.*;

import org.apache.spark.api.java.function.*;

import org.apache.spark.streaming.*;

import org.apache.spark.streaming.api.java.*;

import scala.Tuple2;

// Create a local StreamingContext with two working thread and batch interval of 1 second

SparkConf conf = new SparkConf().setMaster("local[2]").setAppName("NetworkWordCount")

JavaStreamingContext jssc = new JavaStreamingContext(conf, Durations.seconds(1))

{% endhighlight %}

Using this context, we can create a DStream that represents streaming data from a TCP

source, specified as hostname (e.g. `localhost`) and port (e.g. `9999`).

{% highlight java %}

// Create a DStream that will connect to hostname:port, like localhost:9999

JavaReceiverInputDStream lines = jssc.socketTextStream("localhost", 9999);

{% endhighlight %}

This `lines` DStream represents the stream of data that will be received from the data

server. Each record in this stream is a line of text. Then, we want to split the the lines by

space into words.

{% highlight java %}

// Split each line into words

JavaDStream words = lines.flatMap(

new FlatMapFunction() {

@Override public Iterable call(String x) {

return Arrays.asList(x.split(" "));

}

});

{% endhighlight %}

`flatMap` is a DStream operation that creates a new DStream by

generating multiple new records from each record in the source DStream. In this case,

each line will be split into multiple words and the stream of words is represented as the

`words` DStream. Note that we defined the transformation using a

[FlatMapFunction](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.api.java.function.FlatMapFunction) object.

As we will discover along the way, there are a number of such convenience classes in the Java API

that help define DStream transformations.

Next, we want to count these words.

{% highlight java %}

// Count each word in each batch

JavaPairDStream pairs = words.map(

new PairFunction() {

@Override public Tuple2 call(String s) throws Exception {

return new Tuple2(s, 1);

}

});

JavaPairDStream wordCounts = pairs.reduceByKey(

new Function2() {

@Override public Integer call(Integer i1, Integer i2) throws Exception {

return i1 + i2;

}

});

// Print the first ten elements of each RDD generated in this DStream to the console

wordCounts.print();

{% endhighlight %}

The `words` DStream is further mapped (one-to-one transformation) to a DStream of `(word,

1)` pairs, using a [PairFunction](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.api.java.function.PairFunction)

object. Then, it is reduced to get the frequency of words in each batch of data,

using a [Function2](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.api.java.function.Function2) object.

Finally, `wordCounts.print()` will print a few of the counts generated every second.

Note that when these lines are executed, Spark Streaming only sets up the computation it

will perform after it is started, and no real processing has started yet. To start the processing

after all the transformations have been setup, we finally call `start` method.

{% highlight java %}

jssc.start(); // Start the computation

jssc.awaitTermination(); // Wait for the computation to terminate

{% endhighlight %}

The complete code can be found in the Spark Streaming example

[JavaNetworkWordCount]({{site.SPARK_GITHUB_URL}}/blob/master/examples/src/main/java/org/apache/spark/examples/streaming/JavaNetworkWordCount.java).

First, we import [StreamingContext](api/python/pyspark.streaming.html#pyspark.streaming.StreamingContext), which is the main entry point for all streaming functionality. We create a local StreamingContext with two execution threads, and batch interval of 1 second.

{% highlight python %}

from pyspark import SparkContext

from pyspark.streaming import StreamingContext

# Create a local StreamingContext with two working thread and batch interval of 1 second

sc = SparkContext("local[2]", "NetworkWordCount")

ssc = StreamingContext(sc, 1)

{% endhighlight %}

Using this context, we can create a DStream that represents streaming data from a TCP

source, specified as hostname (e.g. `localhost`) and port (e.g. `9999`).

{% highlight python %}

# Create a DStream that will connect to hostname:port, like localhost:9999

lines = ssc.socketTextStream("localhost", 9999)

{% endhighlight %}

This `lines` DStream represents the stream of data that will be received from the data

server. Each record in this DStream is a line of text. Next, we want to split the lines by

space into words.

{% highlight python %}

# Split each line into words

words = lines.flatMap(lambda line: line.split(" "))

{% endhighlight %}

`flatMap` is a one-to-many DStream operation that creates a new DStream by

generating multiple new records from each record in the source DStream. In this case,

each line will be split into multiple words and the stream of words is represented as the

`words` DStream. Next, we want to count these words.

{% highlight python %}

# Count each word in each batch

pairs = words.map(lambda word: (word, 1))

wordCounts = pairs.reduceByKey(lambda x, y: x + y)

# Print the first ten elements of each RDD generated in this DStream to the console

wordCounts.pprint()

{% endhighlight %}

The `words` DStream is further mapped (one-to-one transformation) to a DStream of `(word,

1)` pairs, which is then reduced to get the frequency of words in each batch of data.

Finally, `wordCounts.pprint()` will print a few of the counts generated every second.

Note that when these lines are executed, Spark Streaming only sets up the computation it

will perform when it is started, and no real processing has started yet. To start the processing

after all the transformations have been setup, we finally call

{% highlight python %}

ssc.start() # Start the computation

ssc.awaitTermination() # Wait for the computation to terminate

{% endhighlight %}

The complete code can be found in the Spark Streaming example

[NetworkWordCount]({{site.SPARK_GITHUB_URL}}/blob/master/examples/src/main/python/streaming/network_wordcount.py).

If you have already [downloaded](index.html#downloading) and [built](index.html#building) Spark,

you can run this example as follows. You will first need to run Netcat

(a small utility found in most Unix-like systems) as a data server by using

{% highlight bash %}

$ nc -lk 9999

{% endhighlight %}

Then, in a different terminal, you can start the example by using

{% highlight bash %}

$ ./bin/run-example streaming.NetworkWordCount localhost 9999

{% endhighlight %}

{% highlight bash %}

$ ./bin/run-example streaming.JavaNetworkWordCount localhost 9999

{% endhighlight %}

{% highlight bash %}

$ ./bin/spark-submit examples/src/main/python/streaming/network_wordcount.py localhost 9999

{% endhighlight %}

Then, any lines typed in the terminal running the netcat server will be counted and printed on

screen every second. It will look something like the following.

|

{% highlight bash %}

# TERMINAL 1:

# Running Netcat

$ nc -lk 9999

hello world

...

{% endhighlight %}

|

|

{% highlight bash %}

# TERMINAL 2: RUNNING NetworkWordCount

$ ./bin/run-example streaming.NetworkWordCount localhost 9999

...

-------------------------------------------

Time: 1357008430000 ms

-------------------------------------------

(hello,1)

(world,1)

...

{% endhighlight %}

{% highlight bash %}

# TERMINAL 2: RUNNING JavaNetworkWordCount

$ ./bin/run-example streaming.JavaNetworkWordCount localhost 9999

...

-------------------------------------------

Time: 1357008430000 ms

-------------------------------------------

(hello,1)

(world,1)

...

{% endhighlight %}

{% highlight bash %}

# TERMINAL 2: RUNNING network_wordcount.py

$ ./bin/spark-submit examples/src/main/python/streaming/network_wordcount.py localhost 9999

...

-------------------------------------------

Time: 2014-10-14 15:25:21

-------------------------------------------

(hello,1)

(world,1)

...

{% endhighlight %}

|

***************************************************************************************************

***************************************************************************************************

# Basic Concepts

Next, we move beyond the simple example and elaborate on the basics of Spark Streaming.

## Linking

Similar to Spark, Spark Streaming is available through Maven Central. To write your own Spark Streaming program, you will have to add the following dependency to your SBT or Maven project.

org.apache.spark

spark-streaming_{{site.SCALA_BINARY_VERSION}}

{{site.SPARK_VERSION}}

libraryDependencies += "org.apache.spark" % "spark-streaming_{{site.SCALA_BINARY_VERSION}}" % "{{site.SPARK_VERSION}}"

For ingesting data from sources like Kafka, Flume, and Kinesis that are not present in the Spark

Streaming core

API, you will have to add the corresponding

artifact `spark-streaming-xyz_{{site.SCALA_BINARY_VERSION}}` to the dependencies. For example,

some of the common ones are as follows.

| Source | Artifact |

|---|

| Kafka | spark-streaming-kafka_{{site.SCALA_BINARY_VERSION}} |

| Flume | spark-streaming-flume_{{site.SCALA_BINARY_VERSION}} |

Kinesis

| spark-streaming-kinesis-asl_{{site.SCALA_BINARY_VERSION}} [Amazon Software License] |

| Twitter | spark-streaming-twitter_{{site.SCALA_BINARY_VERSION}} |

| ZeroMQ | spark-streaming-zeromq_{{site.SCALA_BINARY_VERSION}} |

| MQTT | spark-streaming-mqtt_{{site.SCALA_BINARY_VERSION}} |

| |

For an up-to-date list, please refer to the

[Apache repository](http://search.maven.org/#search%7Cga%7C1%7Cg%3A%22org.apache.spark%22%20AND%20v%3A%22{{site.SPARK_VERSION_SHORT}}%22)

for the full list of supported sources and artifacts.

***

## Initializing StreamingContext

To initialize a Spark Streaming program, a **StreamingContext** object has to be created which is the main entry point of all Spark Streaming functionality.

A [StreamingContext](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.streaming.StreamingContext) object can be created from a [SparkConf](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.SparkConf) object.

{% highlight scala %}

import org.apache.spark._

import org.apache.spark.streaming._

val conf = new SparkConf().setAppName(appName).setMaster(master)

val ssc = new StreamingContext(conf, Seconds(1))

{% endhighlight %}

The `appName` parameter is a name for your application to show on the cluster UI.

`master` is a [Spark, Mesos or YARN cluster URL](submitting-applications.html#master-urls),

or a special __"local[\*]"__ string to run in local mode. In practice, when running on a cluster,

you will not want to hardcode `master` in the program,

but rather [launch the application with `spark-submit`](submitting-applications.html) and

receive it there. However, for local testing and unit tests, you can pass "local[\*]" to run Spark Streaming

in-process (detects the number of cores in the local system). Note that this internally creates a [SparkContext](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.SparkContext) (starting point of all Spark functionality) which can be accessed as `ssc.sparkContext`.

The batch interval must be set based on the latency requirements of your application

and available cluster resources. See the [Performance Tuning](#setting-the-right-batch-size)

section for more details.

A `StreamingContext` object can also be created from an existing `SparkContext` object.

{% highlight scala %}

import org.apache.spark.streaming._

val sc = ... // existing SparkContext

val ssc = new StreamingContext(sc, Seconds(1))

{% endhighlight %}

A [JavaStreamingContext](api/java/index.html?org/apache/spark/streaming/api/java/JavaStreamingContext.html) object can be created from a [SparkConf](api/java/index.html?org/apache/spark/SparkConf.html) object.

{% highlight java %}

import org.apache.spark.*;

import org.apache.spark.streaming.api.java.*;

SparkConf conf = new SparkConf().setAppName(appName).setMaster(master);

JavaStreamingContext ssc = new JavaStreamingContext(conf, Duration(1000));

{% endhighlight %}

The `appName` parameter is a name for your application to show on the cluster UI.

`master` is a [Spark, Mesos or YARN cluster URL](submitting-applications.html#master-urls),

or a special __"local[\*]"__ string to run in local mode. In practice, when running on a cluster,

you will not want to hardcode `master` in the program,

but rather [launch the application with `spark-submit`](submitting-applications.html) and

receive it there. However, for local testing and unit tests, you can pass "local[*]" to run Spark Streaming

in-process. Note that this internally creates a [JavaSparkContext](api/java/index.html?org/apache/spark/api/java/JavaSparkContext.html) (starting point of all Spark functionality) which can be accessed as `ssc.sparkContext`.

The batch interval must be set based on the latency requirements of your application

and available cluster resources. See the [Performance Tuning](#setting-the-right-batch-size)

section for more details.

A `JavaStreamingContext` object can also be created from an existing `JavaSparkContext`.

{% highlight java %}

import org.apache.spark.streaming.api.java.*;

JavaSparkContext sc = ... //existing JavaSparkContext

JavaStreamingContext ssc = new JavaStreamingContext(sc, Durations.seconds(1));

{% endhighlight %}

A [StreamingContext](api/python/pyspark.streaming.html#pyspark.streaming.StreamingContext) object can be created from a [SparkContext](api/python/pyspark.html#pyspark.SparkContext) object.

{% highlight python %}

from pyspark import SparkContext

from pyspark.streaming import StreamingContext

sc = SparkContext(master, appName)

ssc = StreamingContext(sc, 1)

{% endhighlight %}

The `appName` parameter is a name for your application to show on the cluster UI.

`master` is a [Spark, Mesos or YARN cluster URL](submitting-applications.html#master-urls),

or a special __"local[\*]"__ string to run in local mode. In practice, when running on a cluster,

you will not want to hardcode `master` in the program,

but rather [launch the application with `spark-submit`](submitting-applications.html) and

receive it there. However, for local testing and unit tests, you can pass "local[\*]" to run Spark Streaming

in-process (detects the number of cores in the local system).

The batch interval must be set based on the latency requirements of your application

and available cluster resources. See the [Performance Tuning](#setting-the-right-batch-size)

section for more details.

After a context is defined, you have to do the following.

1. Define the input sources by creating input DStreams.

1. Define the streaming computations by applying transformation and output operations to DStreams.

1. Start receiving data and processing it using `streamingContext.start()`.

1. Wait for the processing to be stopped (manually or due to any error) using `streamingContext.awaitTermination()`.

1. The processing can be manually stopped using `streamingContext.stop()`.

##### Points to remember:

{:.no_toc}

- Once a context has been started, no new streaming computations can be set up or added to it.

- Once a context has been stopped, it cannot be restarted.

- Only one StreamingContext can be active in a JVM at the same time.

- stop() on StreamingContext also stops the SparkContext. To stop only the StreamingContext, set optional parameter of `stop()` called `stopSparkContext` to false.

- A SparkContext can be re-used to create multiple StreamingContexts, as long as the previous StreamingContext is stopped (without stopping the SparkContext) before the next StreamingContext is created.

***

## Discretized Streams (DStreams)

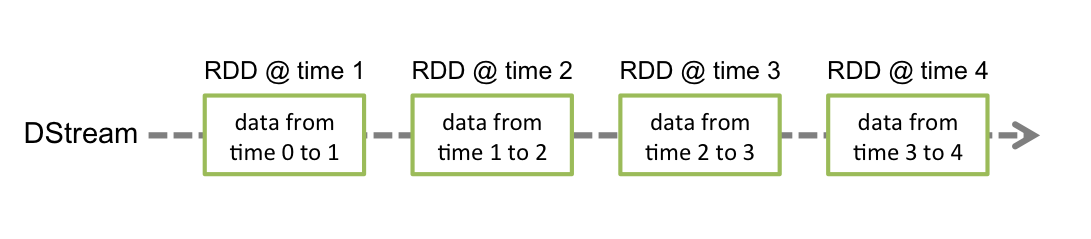

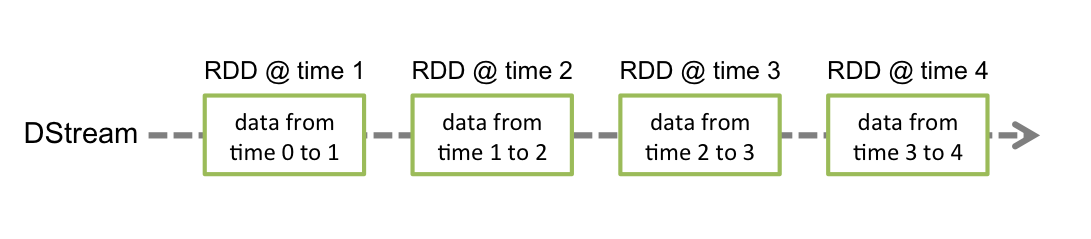

**Discretized Stream** or **DStream** is the basic abstraction provided by Spark Streaming.

It represents a continuous stream of data, either the input data stream received from source,

or the processed data stream generated by transforming the input stream. Internally,

a DStream is represented by a continuous series of RDDs, which is Spark's abstraction of an immutable,

distributed dataset (see [Spark Programming Guide](programming-guide.html#resilient-distributed-datasets-rdds) for more details). Each RDD in a DStream contains data from a certain interval,

as shown in the following figure.

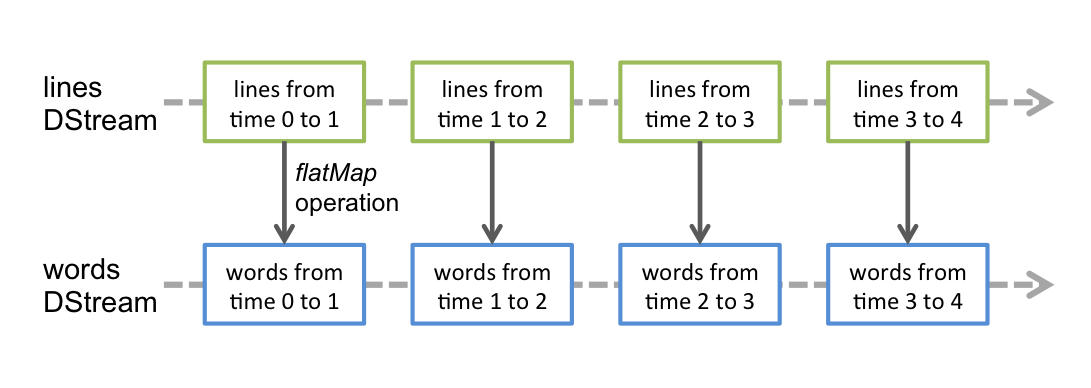

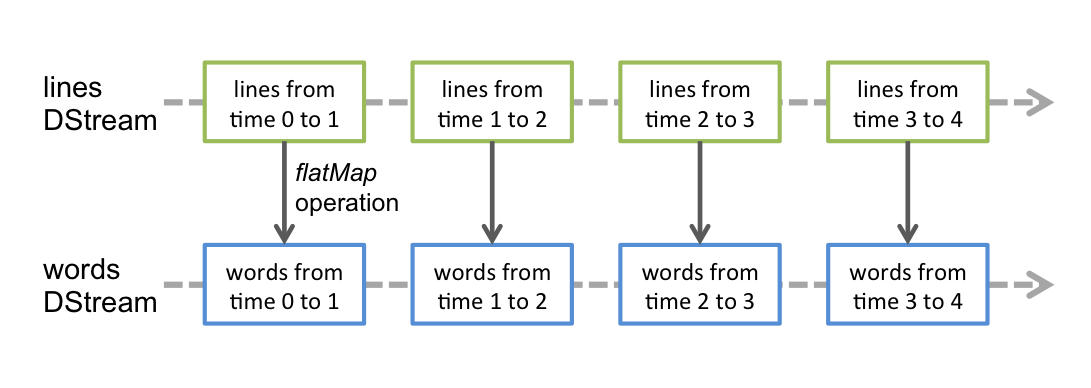

Any operation applied on a DStream translates to operations on the underlying RDDs. For example,

in the [earlier example](#a-quick-example) of converting a stream of lines to words,

the `flatMap` operation is applied on each RDD in the `lines` DStream to generate the RDDs of the

`words` DStream. This is shown in the following figure.

These underlying RDD transformations are computed by the Spark engine. The DStream operations

hide most of these details and provide the developer with higher-level API for convenience.

These operations are discussed in detail in later sections.

***

## Input DStreams and Receivers

Input DStreams are DStreams representing the stream of input data received from streaming

sources. In the [quick example](#a-quick-example), `lines` was an input DStream as it represented

the stream of data received from the netcat server. Every input DStream

(except file stream, discussed later in this section) is associated with a **Receiver**

([Scala doc](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.streaming.receiver.Receiver),

[Java doc](api/java/org/apache/spark/streaming/receiver/Receiver.html)) object which receives the

data from a source and stores it in Spark's memory for processing.

Spark Streaming provides two categories of built-in streaming sources.

- *Basic sources*: Sources directly available in the StreamingContext API.

Example: file systems, socket connections, and Akka actors.

- *Advanced sources*: Sources like Kafka, Flume, Kinesis, Twitter, etc. are available through

extra utility classes. These require linking against extra dependencies as discussed in the

[linking](#linking) section.

We are going to discuss some of the sources present in each category later in this section.

Note that, if you want to receive multiple streams of data in parallel in your streaming

application, you can create multiple input DStreams (discussed

further in the [Performance Tuning](#level-of-parallelism-in-data-receiving) section). This will

create multiple receivers which will simultaneously receive multiple data streams. But note that

Spark worker/executor as a long-running task, hence it occupies one of the cores allocated to the

Spark Streaming application. Hence, it is important to remember that Spark Streaming application

needs to be allocated enough cores (or threads, if running locally) to process the received data,

as well as, to run the receiver(s).

##### Points to remember

{:.no_toc}

- When running a Spark Streaming program locally, do not use "local" or "local[1]" as the master URL.

Either of these means that only one thread will be used for running tasks locally. If you are using

a input DStream based on a receiver (e.g. sockets, Kafka, Flume, etc.), then the single thread will

be used to run the receiver, leaving no thread for processing the received data. Hence, when

running locally, always use "local[*n*]" as the master URL where *n* > number of receivers to run

(see [Spark Properties](configuration.html#spark-properties.html) for information on how to set

the master).

- Extending the logic to running on a cluster, the number of cores allocated to the Spark Streaming

application must be more than the number of receivers. Otherwise the system will receive data, but

not be able to process them.

### Basic Sources

{:.no_toc}

We have already taken a look at the `ssc.socketTextStream(...)` in the [quick example](#a-quick-example)

which creates a DStream from text

data received over a TCP socket connection. Besides sockets, the StreamingContext API provides

methods for creating DStreams from files and Akka actors as input sources.

- **File Streams:** For reading data from files on any file system compatible with the HDFS API (that is, HDFS, S3, NFS, etc.), a DStream can be created as

streamingContext.fileStream[KeyClass, ValueClass, InputFormatClass](dataDirectory)

streamingContext.fileStream(dataDirectory);

streamingContext.textFileStream(dataDirectory)

Spark Streaming will monitor the directory `dataDirectory` and process any files created in that directory (files written in nested directories not supported). Note that

+ The files must have the same data format.

+ The files must be created in the `dataDirectory` by atomically *moving* or *renaming* them into

the data directory.

+ Once moved, the files must not be changed. So if the files are being continuously appended, the new data will not be read.

For simple text files, there is an easier method `streamingContext.textFileStream(dataDirectory)`. And file streams do not require running a receiver, hence does not require allocating cores.

Python API As of Spark 1.2,

`fileStream` is not available in the Python API, only `textFileStream` is available.

- **Streams based on Custom Actors:** DStreams can be created with data streams received through Akka

actors by using `streamingContext.actorStream(actorProps, actor-name)`. See the [Custom Receiver

Guide](streaming-custom-receivers.html) for more details.

Python API Since actors are available only in the Java and Scala

libraries, `actorStream` is not available in the Python API.

- **Queue of RDDs as a Stream:** For testing a Spark Streaming application with test data, one can also create a DStream based on a queue of RDDs, using `streamingContext.queueStream(queueOfRDDs)`. Each RDD pushed into the queue will be treated as a batch of data in the DStream, and processed like a stream.

For more details on streams from sockets, files, and actors,

see the API documentations of the relevant functions in

[StreamingContext](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.streaming.StreamingContext) for

Scala, [JavaStreamingContext](api/java/index.html?org/apache/spark/streaming/api/java/JavaStreamingContext.html)

for Java, and [StreamingContext](api/python/pyspark.streaming.html#pyspark.streaming.StreamingContext) for Python.

### Advanced Sources

{:.no_toc}

Python API As of Spark 1.2,

these sources are not available in the Python API.

This category of sources require interfacing with external non-Spark libraries, some of them with

complex dependencies (e.g., Kafka and Flume). Hence, to minimize issues related to version conflicts

of dependencies, the functionality to create DStreams from these sources have been moved to separate

libraries, that can be [linked](#linking) to explicitly when necessary. For example, if you want to

create a DStream using data from Twitter's stream of tweets, you have to do the following.

1. *Linking*: Add the artifact `spark-streaming-twitter_{{site.SCALA_BINARY_VERSION}}` to the

SBT/Maven project dependencies.

1. *Programming*: Import the `TwitterUtils` class and create a DStream with

`TwitterUtils.createStream` as shown below.

1. *Deploying*: Generate an uber JAR with all the dependencies (including the dependency

`spark-streaming-twitter_{{site.SCALA_BINARY_VERSION}}` and its transitive dependencies) and

then deploy the application. This is further explained in the [Deploying section](#deploying-applications).

{% highlight scala %}

import org.apache.spark.streaming.twitter._

TwitterUtils.createStream(ssc)

{% endhighlight %}

{% highlight java %}

import org.apache.spark.streaming.twitter.*;

TwitterUtils.createStream(jssc);

{% endhighlight %}

Note that these advanced sources are not available in the Spark shell, hence applications based on

these advanced sources cannot be tested in the shell. If you really want to use them in the Spark

shell you will have to download the corresponding Maven artifact's JAR along with its dependencies

and it in the classpath.

Some of these advanced sources are as follows.

- **Twitter:** Spark Streaming's TwitterUtils uses Twitter4j 3.0.3 to get the public stream of tweets using

[Twitter's Streaming API](https://dev.twitter.com/docs/streaming-apis). Authentication information

can be provided by any of the [methods](http://twitter4j.org/en/configuration.html) supported by

Twitter4J library. You can either get the public stream, or get the filtered stream based on a

keywords. See the API documentation ([Scala](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.streaming.twitter.TwitterUtils$),

[Java](api/java/index.html?org/apache/spark/streaming/twitter/TwitterUtils.html)) and examples

([TwitterPopularTags]({{site.SPARK_GITHUB_URL}}/blob/master/examples/src/main/scala/org/apache/spark/examples/streaming/TwitterPopularTags.scala)

and [TwitterAlgebirdCMS]({{site.SPARK_GITHUB_URL}}/blob/master/examples/src/main/scala/org/apache/spark/examples/streaming/TwitterAlgebirdCMS.scala)).

- **Flume:** Spark Streaming {{site.SPARK_VERSION_SHORT}} can received data from Flume 1.4.0. See the [Flume Integration Guide](streaming-flume-integration.html) for more details.

- **Kafka:** Spark Streaming {{site.SPARK_VERSION_SHORT}} can receive data from Kafka 0.8.0. See the [Kafka Integration Guide](streaming-kafka-integration.html) for more details.

- **Kinesis:** See the [Kinesis Integration Guide](streaming-kinesis-integration.html) for more details.

### Custom Sources

{:.no_toc}

Python API As of Spark 1.2,

these sources are not available in the Python API.

Input DStreams can also be created out of custom data sources. All you have to do is implement an

user-defined **receiver** (see next section to understand what that is) that can receive data from

the custom sources and push it into Spark. See the [Custom Receiver

Guide](streaming-custom-receivers.html) for details.

### Receiver Reliability

{:.no_toc}

There can be two kinds of data sources based on their *reliability*. Sources

(like Kafka and Flume) allow the transferred data to be acknowledged. If the system receiving

data from these *reliable* sources acknowledge the received data correctly, it can be ensured

that no data gets lost due to any kind of failure. This leads to two kinds of receivers.

1. *Reliable Receiver* - A *reliable receiver* correctly acknowledges a reliable

source that the data has been received and stored in Spark with replication.

1. *Unreliable Receiver* - These are receivers for sources that do not support acknowledging. Even

for reliable sources, one may implement an unreliable receiver that do not go into the complexity

of acknowledging correctly.

The details of how to write a reliable receiver are discussed in the

[Custom Receiver Guide](streaming-custom-receivers.html).

***

## Transformations on DStreams

Similar to that of RDDs, transformations allow the data from the input DStream to be modified.

DStreams support many of the transformations available on normal Spark RDD's.

Some of the common ones are as follows.

| Transformation | Meaning |

|---|

| map(func) |

Return a new DStream by passing each element of the source DStream through a

function func. |

| flatMap(func) |

Similar to map, but each input item can be mapped to 0 or more output items. |

| filter(func) |

Return a new DStream by selecting only the records of the source DStream on which

func returns true. |

| repartition(numPartitions) |

Changes the level of parallelism in this DStream by creating more or fewer partitions. |

| union(otherStream) |

Return a new DStream that contains the union of the elements in the source DStream and

otherDStream. |

| count() |

Return a new DStream of single-element RDDs by counting the number of elements in each RDD

of the source DStream. |

| reduce(func) |

Return a new DStream of single-element RDDs by aggregating the elements in each RDD of the

source DStream using a function func (which takes two arguments and returns one).

The function should be associative so that it can be computed in parallel. |

| countByValue() |

When called on a DStream of elements of type K, return a new DStream of (K, Long) pairs

where the value of each key is its frequency in each RDD of the source DStream. |

| reduceByKey(func, [numTasks]) |

When called on a DStream of (K, V) pairs, return a new DStream of (K, V) pairs where the

values for each key are aggregated using the given reduce function. Note: By default,

this uses Spark's default number of parallel tasks (2 for local mode, and in cluster mode the number

is determined by the config property spark.default.parallelism) to do the grouping.

You can pass an optional numTasks argument to set a different number of tasks. |

| join(otherStream, [numTasks]) |

When called on two DStreams of (K, V) and (K, W) pairs, return a new DStream of (K, (V, W))

pairs with all pairs of elements for each key. |

| cogroup(otherStream, [numTasks]) |

When called on DStream of (K, V) and (K, W) pairs, return a new DStream of

(K, Seq[V], Seq[W]) tuples. |

| transform(func) |

Return a new DStream by applying a RDD-to-RDD function to every RDD of the source DStream.

This can be used to do arbitrary RDD operations on the DStream. |

| updateStateByKey(func) |

Return a new "state" DStream where the state for each key is updated by applying the

given function on the previous state of the key and the new values for the key. This can be

used to maintain arbitrary state data for each key. |

| |

The last two transformations are worth highlighting again.

#### UpdateStateByKey Operation

{:.no_toc}

The `updateStateByKey` operation allows you to maintain arbitrary state while continuously updating

it with new information. To use this, you will have to do two steps.

1. Define the state - The state can be of arbitrary data type.

1. Define the state update function - Specify with a function how to update the state using the

previous state and the new values from input stream.

Let's illustrate this with an example. Say you want to maintain a running count of each word

seen in a text data stream. Here, the running count is the state and it is an integer. We

define the update function as

{% highlight scala %}

def updateFunction(newValues: Seq[Int], runningCount: Option[Int]): Option[Int] = {

val newCount = ... // add the new values with the previous running count to get the new count

Some(newCount)

}

{% endhighlight %}

This is applied on a DStream containing words (say, the `pairs` DStream containing `(word,

1)` pairs in the [earlier example](#a-quick-example)).

{% highlight scala %}

val runningCounts = pairs.updateStateByKey[Int](updateFunction _)

{% endhighlight %}

The update function will be called for each word, with `newValues` having a sequence of 1's (from

the `(word, 1)` pairs) and the `runningCount` having the previous count. For the complete

Scala code, take a look at the example

[StatefulNetworkWordCount.scala]({{site.SPARK_GITHUB_URL}}/blob/master/examples/src/main/scala/org/apache

/spark/examples/streaming/StatefulNetworkWordCount.scala).

{% highlight java %}

import com.google.common.base.Optional;

Function2, Optional, Optional> updateFunction =

new Function2, Optional, Optional>() {

@Override public Optional call(List values, Optional state) {

Integer newSum = ... // add the new values with the previous running count to get the new count

return Optional.of(newSum);

}

};

{% endhighlight %}

This is applied on a DStream containing words (say, the `pairs` DStream containing `(word,

1)` pairs in the [quick example](#a-quick-example)).

{% highlight java %}

JavaPairDStream runningCounts = pairs.updateStateByKey(updateFunction);

{% endhighlight %}

The update function will be called for each word, with `newValues` having a sequence of 1's (from

the `(word, 1)` pairs) and the `runningCount` having the previous count. For the complete

Java code, take a look at the example

[JavaStatefulNetworkWordCount.java]({{site.SPARK_GITHUB_URL}}/blob/master/examples/src/main/java/org/apache/spark/examples/streaming

/JavaStatefulNetworkWordCount.java).

{% highlight python %}

def updateFunction(newValues, runningCount):

if runningCount is None:

runningCount = 0

return sum(newValues, runningCount) # add the new values with the previous running count to get the new count

{% endhighlight %}

This is applied on a DStream containing words (say, the `pairs` DStream containing `(word,

1)` pairs in the [earlier example](#a-quick-example)).

{% highlight python %}

runningCounts = pairs.updateStateByKey(updateFunction)

{% endhighlight %}

The update function will be called for each word, with `newValues` having a sequence of 1's (from

the `(word, 1)` pairs) and the `runningCount` having the previous count. For the complete

Python code, take a look at the example

[stateful_network_wordcount.py]({{site.SPARK_GITHUB_URL}}/blob/master/examples/src/main/python/streaming/stateful_network_wordcount.py).

Note that using `updateStateByKey` requires the checkpoint directory to be configured, which is

discussed in detail in the [checkpointing](#checkpointing) section.

#### Transform Operation

{:.no_toc}

The `transform` operation (along with its variations like `transformWith`) allows

arbitrary RDD-to-RDD functions to be applied on a DStream. It can be used to apply any RDD

operation that is not exposed in the DStream API.

For example, the functionality of joining every batch in a data stream

with another dataset is not directly exposed in the DStream API. However,

you can easily use `transform` to do this. This enables very powerful possibilities. For example,

if you want to do real-time data cleaning by joining the input data stream with precomputed

spam information (maybe generated with Spark as well) and then filtering based on it.

{% highlight scala %}

val spamInfoRDD = ssc.sparkContext.newAPIHadoopRDD(...) // RDD containing spam information

val cleanedDStream = wordCounts.transform(rdd => {

rdd.join(spamInfoRDD).filter(...) // join data stream with spam information to do data cleaning

...

})

{% endhighlight %}

{% highlight java %}

import org.apache.spark.streaming.api.java.*;

// RDD containing spam information

final JavaPairRDD spamInfoRDD = jssc.sparkContext().newAPIHadoopRDD(...);

JavaPairDStream cleanedDStream = wordCounts.transform(

new Function, JavaPairRDD>() {

@Override public JavaPairRDD call(JavaPairRDD rdd) throws Exception {

rdd.join(spamInfoRDD).filter(...); // join data stream with spam information to do data cleaning

...

}

});

{% endhighlight %}

{% highlight python %}

spamInfoRDD = sc.pickleFile(...) # RDD containing spam information

# join data stream with spam information to do data cleaning

cleanedDStream = wordCounts.transform(lambda rdd: rdd.join(spamInfoRDD).filter(...))

{% endhighlight %}

In fact, you can also use [machine learning](mllib-guide.html) and

[graph computation](graphx-programming-guide.html) algorithms in the `transform` method.

#### Window Operations

{:.no_toc}

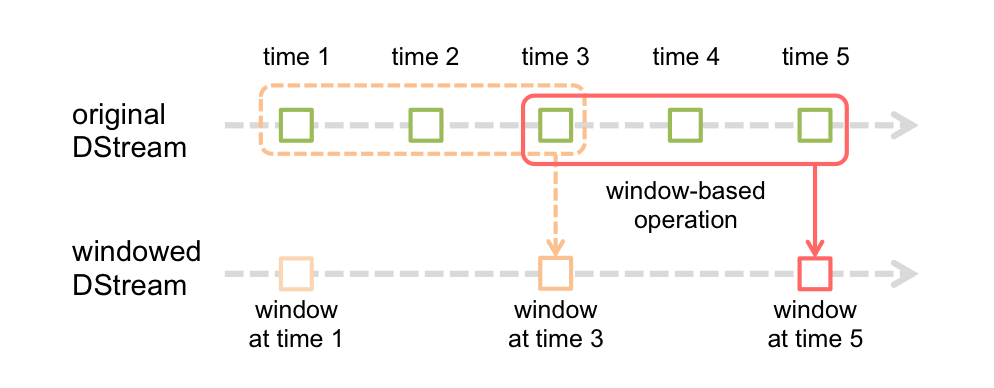

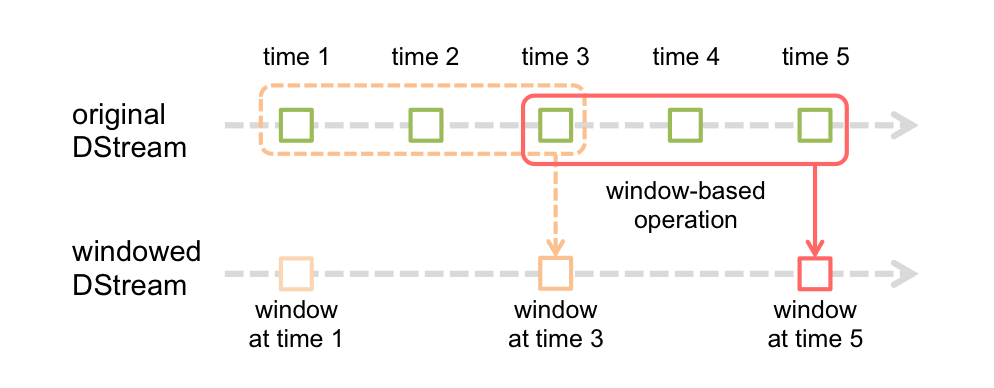

Finally, Spark Streaming also provides *windowed computations*, which allow you to apply

transformations over a sliding window of data. This following figure illustrates this sliding

window.

As shown in the figure, every time the window *slides* over a source DStream,

the source RDDs that fall within the window are combined and operated upon to produce the

RDDs of the windowed DStream. In this specific case, the operation is applied over last 3 time

units of data, and slides by 2 time units. This shows that any window operation needs to

specify two parameters.

* window length - The duration of the window (3 in the figure)

* sliding interval - The interval at which the window operation is performed (2 in

the figure).

These two parameters must be multiples of the batch interval of the source DStream (1 in the

figure).

Let's illustrate the window operations with an example. Say, you want to extend the

[earlier example](#a-quick-example) by generating word counts over last 30 seconds of data,

every 10 seconds. To do this, we have to apply the `reduceByKey` operation on the `pairs` DStream of

`(word, 1)` pairs over the last 30 seconds of data. This is done using the

operation `reduceByKeyAndWindow`.

{% highlight scala %}

// Reduce last 30 seconds of data, every 10 seconds

val windowedWordCounts = pairs.reduceByKeyAndWindow((a:Int,b:Int) => (a + b), Seconds(30), Seconds(10))

{% endhighlight %}

{% highlight java %}

// Reduce function adding two integers, defined separately for clarity

Function2 reduceFunc = new Function2() {

@Override public Integer call(Integer i1, Integer i2) throws Exception {

return i1 + i2;

}

};

// Reduce last 30 seconds of data, every 10 seconds

JavaPairDStream windowedWordCounts = pairs.reduceByKeyAndWindow(reduceFunc, Durations.seconds(30), Durations.seconds(10));

{% endhighlight %}

{% highlight python %}

# Reduce last 30 seconds of data, every 10 seconds

windowedWordCounts = pairs.reduceByKeyAndWindow(lambda x, y: x + y, lambda x, y: x - y, 30, 10)

{% endhighlight %}

Some of the common window operations are as follows. All of these operations take the

said two parameters - windowLength and slideInterval.

| Transformation | Meaning |

|---|

| window(windowLength, slideInterval) |

Return a new DStream which is computed based on windowed batches of the source DStream.

|

| countByWindow(windowLength, slideInterval) |

Return a sliding window count of elements in the stream.

|

| reduceByWindow(func, windowLength, slideInterval) |

Return a new single-element stream, created by aggregating elements in the stream over a

sliding interval using func. The function should be associative so that it can be computed

correctly in parallel.

|

| reduceByKeyAndWindow(func, windowLength, slideInterval,

[numTasks]) |

When called on a DStream of (K, V) pairs, returns a new DStream of (K, V)

pairs where the values for each key are aggregated using the given reduce function func

over batches in a sliding window. Note: By default, this uses Spark's default number of

parallel tasks (2 for local mode, and in cluster mode the number is determined by the config

property spark.default.parallelism) to do the grouping. You can pass an optional

numTasks argument to set a different number of tasks.

|

| reduceByKeyAndWindow(func, invFunc, windowLength,

slideInterval, [numTasks]) |

A more efficient version of the above reduceByKeyAndWindow() where the reduce

value of each window is calculated incrementally using the reduce values of the previous window.

This is done by reducing the new data that enter the sliding window, and "inverse reducing" the

old data that leave the window. An example would be that of "adding" and "subtracting" counts

of keys as the window slides. However, it is applicable to only "invertible reduce functions",

that is, those reduce functions which have a corresponding "inverse reduce" function (taken as

parameter invFunc. Like in reduceByKeyAndWindow, the number of reduce tasks

is configurable through an optional argument. Note that [checkpointing](#checkpointing) must be

enabled for using this operation.

|

| countByValueAndWindow(windowLength,

slideInterval, [numTasks]) |

When called on a DStream of (K, V) pairs, returns a new DStream of (K, Long) pairs where the

value of each key is its frequency within a sliding window. Like in

reduceByKeyAndWindow, the number of reduce tasks is configurable through an

optional argument.

|

| |

The complete list of DStream transformations is available in the API documentation. For the Scala API,

see [DStream](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.streaming.dstream.DStream)

and [PairDStreamFunctions](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.streaming.dstream.PairDStreamFunctions).

For the Java API, see [JavaDStream](api/java/index.html?org/apache/spark/streaming/api/java/JavaDStream.html)

and [JavaPairDStream](api/java/index.html?org/apache/spark/streaming/api/java/JavaPairDStream.html).

For the Python API, see [DStream](api/python/pyspark.streaming.html#pyspark.streaming.DStream).

***

## Output Operations on DStreams

Output operations allow DStream's data to be pushed out external systems like a database or a file systems.

Since the output operations actually allow the transformed data to be consumed by external systems,

they trigger the actual execution of all the DStream transformations (similar to actions for RDDs).

Currently, the following output operations are defined:

| Output Operation | Meaning |

|---|

| print() |

Prints first ten elements of every batch of data in a DStream on the driver node running

the streaming application. This is useful for development and debugging.

Python API This is called

pprint() in the Python API.

|

| saveAsTextFiles(prefix, [suffix]) |

Save this DStream's contents as a text files. The file name at each batch interval is

generated based on prefix and suffix: "prefix-TIME_IN_MS[.suffix]". |

| saveAsObjectFiles(prefix, [suffix]) |

Save this DStream's contents as a SequenceFile of serialized Java objects. The file

name at each batch interval is generated based on prefix and

suffix: "prefix-TIME_IN_MS[.suffix]".

Python API This is not available in

the Python API.

|

| saveAsHadoopFiles(prefix, [suffix]) |

Save this DStream's contents as a Hadoop file. The file name at each batch interval is

generated based on prefix and suffix: "prefix-TIME_IN_MS[.suffix]".

Python API This is not available in

the Python API.

|

| foreachRDD(func) |

The most generic output operator that applies a function, func, to each RDD generated from

the stream. This function should push the data in each RDD to a external system, like saving the RDD to

files, or writing it over the network to a database. Note that the function func is executed

in the driver process running the streaming application, and will usually have RDD actions in it

that will force the computation of the streaming RDDs. |

| |

### Design Patterns for using foreachRDD

{:.no_toc}

`dstream.foreachRDD` is a powerful primitive that allows data to sent out to external systems.

However, it is important to understand how to use this primitive correctly and efficiently.

Some of the common mistakes to avoid are as follows.

Often writing data to external system requires creating a connection object

(e.g. TCP connection to a remote server) and using it to send data to a remote system.

For this purpose, a developer may inadvertently try creating a connection object at

the Spark driver, but try to use it in a Spark worker to save records in the RDDs.

For example (in Scala),

{% highlight scala %}

dstream.foreachRDD { rdd =>

val connection = createNewConnection() // executed at the driver

rdd.foreach { record =>

connection.send(record) // executed at the worker

}

}

{% endhighlight %}

{% highlight python %}

def sendRecord(rdd):

connection = createNewConnection() # executed at the driver

rdd.foreach(lambda record: connection.send(record))

connection.close()

dstream.foreachRDD(sendRecord)

{% endhighlight %}

This is incorrect as this requires the connection object to be serialized and sent from the

driver to the worker. Such connection objects are rarely transferrable across machines. This

error may manifest as serialization errors (connection object not serializable), initialization

errors (connection object needs to be initialized at the workers), etc. The correct solution is

to create the connection object at the worker.

However, this can lead to another common mistake - creating a new connection for every record.

For example,

{% highlight scala %}

dstream.foreachRDD { rdd =>

rdd.foreach { record =>

val connection = createNewConnection()

connection.send(record)

connection.close()

}

}

{% endhighlight %}

{% highlight python %}

def sendRecord(record):

connection = createNewConnection()

connection.send(record)

connection.close()

dstream.foreachRDD(lambda rdd: rdd.foreach(sendRecord))

{% endhighlight %}

Typically, creating a connection object has time and resource overheads. Therefore, creating and

destroying a connection object for each record can incur unnecessarily high overheads and can

significantly reduce the overall throughput of the system. A better solution is to use

`rdd.foreachPartition` - create a single connection object and send all the records in a RDD

partition using that connection.

{% highlight scala %}

dstream.foreachRDD { rdd =>

rdd.foreachPartition { partitionOfRecords =>

val connection = createNewConnection()

partitionOfRecords.foreach(record => connection.send(record))

connection.close()

}

}

{% endhighlight %}

{% highlight python %}

def sendPartition(iter):

connection = createNewConnection()

for record in iter:

connection.send(record)

connection.close()

dstream.foreachRDD(lambda rdd: rdd.foreachPartition(sendPartition))

{% endhighlight %}

This amortizes the connection creation overheads over many records.

Finally, this can be further optimized by reusing connection objects across multiple RDDs/batches.

One can maintain a static pool of connection objects than can be reused as

RDDs of multiple batches are pushed to the external system, thus further reducing the overheads.

{% highlight scala %}

dstream.foreachRDD { rdd =>

rdd.foreachPartition { partitionOfRecords =>

// ConnectionPool is a static, lazily initialized pool of connections

val connection = ConnectionPool.getConnection()

partitionOfRecords.foreach(record => connection.send(record))

ConnectionPool.returnConnection(connection) // return to the pool for future reuse

}

}

{% endhighlight %}

{% highlight python %}

def sendPartition(iter):

# ConnectionPool is a static, lazily initialized pool of connections

connection = ConnectionPool.getConnection()

for record in iter:

connection.send(record)

# return to the pool for future reuse

ConnectionPool.returnConnection(connection)

dstream.foreachRDD(lambda rdd: rdd.foreachPartition(sendPartition))

{% endhighlight %}

Note that the connections in the pool should be lazily created on demand and timed out if not used for a while. This achieves the most efficient sending of data to external systems.

##### Other points to remember:

{:.no_toc}

- DStreams are executed lazily by the output operations, just like RDDs are lazily executed by RDD actions. Specifically, RDD actions inside the DStream output operations force the processing of the received data. Hence, if your application does not have any output operation, or has output operations like `dstream.foreachRDD()` without any RDD action inside them, then nothing will get executed. The system will simply receive the data and discard it.

- By default, output operations are executed one-at-a-time. And they are executed in the order they are defined in the application.

***

## Caching / Persistence

Similar to RDDs, DStreams also allow developers to persist the stream's data in memory. That is,

using `persist()` method on a DStream will automatically persist every RDD of that DStream in

memory. This is useful if the data in the DStream will be computed multiple times (e.g., multiple

operations on the same data). For window-based operations like `reduceByWindow` and

`reduceByKeyAndWindow` and state-based operations like `updateStateByKey`, this is implicitly true.

Hence, DStreams generated by window-based operations are automatically persisted in memory, without

the developer calling `persist()`.

For input streams that receive data over the network (such as, Kafka, Flume, sockets, etc.), the

default persistence level is set to replicate the data to two nodes for fault-tolerance.

Note that, unlike RDDs, the default persistence level of DStreams keeps the data serialized in

memory. This is further discussed in the [Performance Tuning](#memory-tuning) section. More

information on different persistence levels can be found in

[Spark Programming Guide](programming-guide.html#rdd-persistence).

***

## Checkpointing

A streaming application must operate 24/7 and hence must be resilient to failures unrelated

to the application logic (e.g., system failures, JVM crashes, etc.). For this to be possible,

Spark Streaming needs to *checkpoints* enough information to a fault-

tolerant storage system such that it can recover from failures. There are two types of data

that are checkpointed.

- *Metadata checkpointing* - Saving of the information defining the streaming computation to

fault-tolerant storage like HDFS. This is used to recover from failure of the node running the

driver of the streaming application (discussed in detail later). Metadata includes:

+ *Configuration* - The configuration that were used to create the streaming application.

+ *DStream operations* - The set of DStream operations that define the streaming application.

+ *Incomplete batches* - Batches whose jobs are queued but have not completed yet.

- *Data checkpointing* - Saving of the generated RDDs to reliable storage. This is necessary

in some *stateful* transformations that combine data across multiple batches. In such

transformations, the generated RDDs depends on RDDs of previous batches, which causes the length

of the dependency chain to keep increasing with time. To avoid such unbounded increase in recovery

time (proportional to dependency chain), intermediate RDDs of stateful transformations are periodically

*checkpointed* to reliable storage (e.g. HDFS) to cut off the dependency chains.

To summarize, metadata checkpointing is primarily needed for recovery from driver failures,

whereas data or RDD checkpointing is necessary even for basic functioning if stateful

transformations are used.

#### When to enable Checkpointing

{:.no_toc}

Checkpointing must be enabled for applications with any of the following requirements:

- *Usage of stateful transformations* - If either `updateStateByKey` or `reduceByKeyAndWindow` (with

inverse function) is used in the application, then the checkpoint directory must be provided for

allowing periodic RDD checkpointing.

- *Recovering from failures of the driver running the application* - Metadata checkpoints are used

for to recover with progress information.

Note that simple streaming applications without the aforementioned stateful transformations can be

run without enabling checkpointing. The recovery from driver failures will also be partial in

that case (some received but unprocessed data may be lost). This is often acceptable and many run

Spark Streaming applications in this way. Support for non-Hadoop environments is expected

to improve in the future.

#### How to configure Checkpointing

{:.no_toc}

Checkpointing can be enabled by setting a directory in a fault-tolerant,

reliable file system (e.g., HDFS, S3, etc.) to which the checkpoint information will be saved.

This is done by using `streamingContext.checkpoint(checkpointDirectory)`. This will allow you to

use the aforementioned stateful transformations. Additionally,

if you want make the application recover from driver failures, you should rewrite your

streaming application to have the following behavior.

+ When the program is being started for the first time, it will create a new StreamingContext,

set up all the streams and then call start().

+ When the program is being restarted after failure, it will re-create a StreamingContext

from the checkpoint data in the checkpoint directory.

This behavior is made simple by using `StreamingContext.getOrCreate`. This is used as follows.

{% highlight scala %}

// Function to create and setup a new StreamingContext

def functionToCreateContext(): StreamingContext = {

val ssc = new StreamingContext(...) // new context

val lines = ssc.socketTextStream(...) // create DStreams

...

ssc.checkpoint(checkpointDirectory) // set checkpoint directory

ssc

}

// Get StreamingContext from checkpoint data or create a new one

val context = StreamingContext.getOrCreate(checkpointDirectory, functionToCreateContext _)

// Do additional setup on context that needs to be done,

// irrespective of whether it is being started or restarted

context. ...

// Start the context

context.start()

context.awaitTermination()

{% endhighlight %}

If the `checkpointDirectory` exists, then the context will be recreated from the checkpoint data.

If the directory does not exist (i.e., running for the first time),

then the function `functionToCreateContext` will be called to create a new

context and set up the DStreams. See the Scala example

[RecoverableNetworkWordCount]({{site.SPARK_GITHUB_URL}}/tree/master/examples/src/main/scala/org/apache/spark/examples/streaming/RecoverableNetworkWordCount.scala).

This example appends the word counts of network data into a file.

This behavior is made simple by using `JavaStreamingContext.getOrCreate`. This is used as follows.

{% highlight java %}

// Create a factory object that can create a and setup a new JavaStreamingContext

JavaStreamingContextFactory contextFactory = new JavaStreamingContextFactory() {

@Override public JavaStreamingContext create() {

JavaStreamingContext jssc = new JavaStreamingContext(...); // new context

JavaDStream lines = jssc.socketTextStream(...); // create DStreams

...

jssc.checkpoint(checkpointDirectory); // set checkpoint directory

return jssc;

}

};

// Get JavaStreamingContext from checkpoint data or create a new one

JavaStreamingContext context = JavaStreamingContext.getOrCreate(checkpointDirectory, contextFactory);

// Do additional setup on context that needs to be done,

// irrespective of whether it is being started or restarted

context. ...

// Start the context

context.start();

context.awaitTermination();

{% endhighlight %}

If the `checkpointDirectory` exists, then the context will be recreated from the checkpoint data.

If the directory does not exist (i.e., running for the first time),

then the function `contextFactory` will be called to create a new

context and set up the DStreams. See the Scala example

[JavaRecoverableNetworkWordCount]({{site.SPARK_GITHUB_URL}}/tree/master/examples/src/main/java/org/apache/spark/examples/streaming/JavaRecoverableNetworkWordCount.java).

This example appends the word counts of network data into a file.

This behavior is made simple by using `StreamingContext.getOrCreate`. This is used as follows.

{% highlight python %}

# Function to create and setup a new StreamingContext

def functionToCreateContext():

sc = SparkContext(...) # new context

ssc = new StreamingContext(...)

lines = ssc.socketTextStream(...) # create DStreams

...

ssc.checkpoint(checkpointDirectory) # set checkpoint directory

return ssc

# Get StreamingContext from checkpoint data or create a new one

context = StreamingContext.getOrCreate(checkpointDirectory, functionToCreateContext)

# Do additional setup on context that needs to be done,

# irrespective of whether it is being started or restarted

context. ...

# Start the context

context.start()

context.awaitTermination()

{% endhighlight %}

If the `checkpointDirectory` exists, then the context will be recreated from the checkpoint data.

If the directory does not exist (i.e., running for the first time),

then the function `functionToCreateContext` will be called to create a new

context and set up the DStreams. See the Python example

[recoverable_network_wordcount.py]({{site.SPARK_GITHUB_URL}}/tree/master/examples/src/main/python/streaming/recoverable_network_wordcount.py).

This example appends the word counts of network data into a file.

You can also explicitly create a `StreamingContext` from the checkpoint data and start the

computation by using `StreamingContext.getOrCreate(checkpointDirectory, None)`.

In addition to using `getOrCreate` one also needs to ensure that the driver process gets

restarted automatically on failure. This can only be done by the deployment infrastructure that is

used to run the application. This is further discussed in the

[Deployment](#deploying-applications.html) section.

Note that checkpointing of RDDs incurs the cost of saving to reliable storage.

This may cause an increase in the processing time of those batches where RDDs get checkpointed.

Hence, the interval of

checkpointing needs to be set carefully. At small batch sizes (say 1 second), checkpointing every

batch may significantly reduce operation throughput. Conversely, checkpointing too infrequently

causes the lineage and task sizes to grow which may have detrimental effects. For stateful

transformations that require RDD checkpointing, the default interval is a multiple of the

batch interval that is at least 10 seconds. It can be set by using

`dstream.checkpoint(checkpointInterval)`. Typically, a checkpoint interval of 5 - 10 times of

sliding interval of a DStream is good setting to try.

***

## Deploying Applications

This section discusses the steps to deploy a Spark Streaming application.

### Requirements

{:.no_toc}

To run a Spark Streaming applications, you need to have the following.

- *Cluster with a cluster manager* - This is the general requirement of any Spark application,

and discussed in detail in the [deployment guide](cluster-overview.html).

- *Package the application JAR* - You have to compile your streaming application into a JAR.

If you are using [`spark-submit`](submitting-applications.html) to start the

application, then you will not need to provide Spark and Spark Streaming in the JAR. However,

if your application uses [advanced sources](#advanced-sources) (e.g. Kafka, Flume, Twitter),

then you will have to package the extra artifact they link to, along with their dependencies,

in the JAR that is used to deploy the application. For example, an application using `TwitterUtils`

will have to include `spark-streaming-twitter_{{site.SCALA_BINARY_VERSION}}` and all its

transitive dependencies in the application JAR.

- *Configuring sufficient memory for the executors* - Since the received data must be stored in

memory, the executors must be configured with sufficient memory to hold the received data. Note

that if you are doing 10 minute window operations, the system has to keep at least last 10 minutes

of data in memory. So the memory requirements for the application depends on the operations

used in it.

- *Configuring checkpointing* - If the stream application requires it, then a directory in the

Hadoop API compatible fault-tolerant storage (e.g. HDFS, S3, etc.) must be configured as the

checkpoint directory and the streaming application written in a way that checkpoint

information can be used for failure recovery. See the [checkpointing](#checkpointing) section

for more details.

- *Configuring automatic restart of the application driver* - To automatically recover from a

driver failure, the deployment infrastructure that is

used to run the streaming application must monitor the driver process and relaunch the driver

if it fails. Different [cluster managers](cluster-overview.html#cluster-manager-types)

have different tools to achieve this.

+ *Spark Standalone* - A Spark application driver can be submitted to run within the Spark

Standalone cluster (see

[cluster deploy mode](spark-standalone.html#launching-spark-applications)), that is, the

application driver itself runs on one of the worker nodes. Furthermore, the

Standalone cluster manager can be instructed to *supervise* the driver,

and relaunch it if the driver fails either due to non-zero exit code,

or due to failure of the node running the driver. See *cluster mode* and *supervise* in the

[Spark Standalone guide](spark-standalone.html) for more details.

+ *YARN* - Yarn supports a similar mechanism for automatically restarting an application.

Please refer to YARN documentation for more details.

+ *Mesos* - [Marathon](https://github.com/mesosphere/marathon) has been used to achieve this

with Mesos.

- *[Experimental in Spark 1.2] Configuring write ahead logs* - In Spark 1.2,

we have introduced a new experimental feature of write ahead logs for achieving strong

fault-tolerance guarantees. If enabled, all the data received from a receiver gets written into

a write ahead log in the configuration checkpoint directory. This prevents data loss on driver

recovery, thus ensuring zero data loss (discussed in detail in the

[Fault-tolerance Semantics](#fault-tolerance-semantics) section). This can be enabled by setting

the [configuration parameter](configuration.html#spark-streaming)

`spark.streaming.receiver.writeAheadLog.enable` to `true`. However, these stronger semantics may

come at the cost of the receiving throughput of individual receivers. This can be corrected by

running [more receivers in parallel](#level-of-parallelism-in-data-receiving)

to increase aggregate throughput. Additionally, it is recommended that the replication of the

received data within Spark be disabled when the write ahead log is enabled as the log is already

stored in a replicated storage system. This can be done by setting the storage level for the

input stream to `StorageLevel.MEMORY_AND_DISK_SER`.

### Upgrading Application Code

{:.no_toc}

If a running Spark Streaming application needs to be upgraded with new

application code, then there are two possible mechanism.

- The upgraded Spark Streaming application is started and run in parallel to the existing application.

Once the new one (receiving the same data as the old one) has been warmed up and ready

for prime time, the old one be can be brought down. Note that this can be done for data sources that support

sending the data to two destinations (i.e., the earlier and upgraded applications).

- The existing application is shutdown gracefully (see

[`StreamingContext.stop(...)`](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.streaming.StreamingContext)

or [`JavaStreamingContext.stop(...)`](api/java/index.html?org/apache/spark/streaming/api/java/JavaStreamingContext.html)

for graceful shutdown options) which ensure data that have been received is completely

processed before shutdown. Then the

upgraded application can be started, which will start processing from the same point where the earlier

application left off. Note that this can be done only with input sources that support source-side buffering

(like Kafka, and Flume) as data needs to be buffered while the previous application was down and

the upgraded application is not yet up. And restarting from earlier checkpoint

information of pre-upgrade code cannot be done. The checkpoint information essentially

contains serialized Scala/Java/Python objects and trying to deserialize objects with new,

modified classes may lead to errors. In this case, either start the upgraded app with a different

checkpoint directory, or delete the previous checkpoint directory.

### Other Considerations

{:.no_toc}

If the data is being received by the receivers faster than what can be processed,

you can limit the rate by setting the [configuration parameter](configuration.html#spark-streaming)

`spark.streaming.receiver.maxRate`.

***

## Monitoring Applications

Beyond Spark's [monitoring capabilities](monitoring.html), there are additional capabilities

specific to Spark Streaming. When a StreamingContext is used, the

[Spark web UI](monitoring.html#web-interfaces) shows

an additional `Streaming` tab which shows statistics about running receivers (whether

receivers are active, number of records received, receiver error, etc.)

and completed batches (batch processing times, queueing delays, etc.). This can be used to

monitor the progress of the streaming application.

The following two metrics in web UI are particularly important:

- *Processing Time* - The time to process each batch of data.

- *Scheduling Delay* - the time a batch waits in a queue for the processing of previous batches

to finish.

If the batch processing time is consistently more than the batch interval and/or the queueing

delay keeps increasing, then it indicates the system is

not able to process the batches as fast they are being generated and falling behind.

In that case, consider

[reducing](#reducing-the-processing-time-of-each-batch) the batch processing time.

The progress of a Spark Streaming program can also be monitored using the

[StreamingListener](api/scala/index.html#org.apache.spark.scheduler.StreamingListener) interface,

which allows you to get receiver status and processing times. Note that this is a developer API

and it is likely to be improved upon (i.e., more information reported) in the future.

***************************************************************************************************

***************************************************************************************************

# Performance Tuning

Getting the best performance of a Spark Streaming application on a cluster requires a bit of

tuning. This section explains a number of the parameters and configurations that can tuned to

improve the performance of you application. At a high level, you need to consider two things:

1. Reducing the processing time of each batch of data by efficiently using cluster resources.

2. Setting the right batch size such that the batches of data can be processed as fast as they

are received (that is, data processing keeps up with the data ingestion).

## Reducing the Processing Time of each Batch

There are a number of optimizations that can be done in Spark to minimize the processing time of

each batch. These have been discussed in detail in [Tuning Guide](tuning.html). This section

highlights some of the most important ones.

### Level of Parallelism in Data Receiving

{:.no_toc}

Receiving data over the network (like Kafka, Flume, socket, etc.) requires the data to deserialized

and stored in Spark. If the data receiving becomes a bottleneck in the system, then consider

parallelizing the data receiving. Note that each input DStream

creates a single receiver (running on a worker machine) that receives a single stream of data.

Receiving multiple data streams can therefore be achieved by creating multiple input DStreams

and configuring them to receive different partitions of the data stream from the source(s).

For example, a single Kafka input DStream receiving two topics of data can be split into two

Kafka input streams, each receiving only one topic. This would run two receivers on two workers,

thus allowing data to be received in parallel, and increasing overall throughput. These multiple

DStream can be unioned together to create a single DStream. Then the transformations that was

being applied on the single input DStream can applied on the unified stream. This is done as follows.

{% highlight scala %}

val numStreams = 5

val kafkaStreams = (1 to numStreams).map { i => KafkaUtils.createStream(...) }

val unifiedStream = streamingContext.union(kafkaStreams)

unifiedStream.print()

{% endhighlight %}

{% highlight java %}

int numStreams = 5;

List> kafkaStreams = new ArrayList>(numStreams);

for (int i = 0; i < numStreams; i++) {

kafkaStreams.add(KafkaUtils.createStream(...));

}

JavaPairDStream unifiedStream = streamingContext.union(kafkaStreams.get(0), kafkaStreams.subList(1, kafkaStreams.size()));

unifiedStream.print();

{% endhighlight %}

Another parameter that should be considered is the receiver's blocking interval,

which is determined by the [configuration parameter](configuration.html#spark-streaming)

`spark.streaming.blockInterval`. For most receivers, the received data is coalesced together into

blocks of data before storing inside Spark's memory. The number of blocks in each batch

determines the number of tasks that will be used to process those